The Writing Process: A Checklist

Because writing is a complex task, effective writing involves more than just sitting down and writing something. To do your best writing, work on your writing assignments in stages. Use this checklist to understand the process.

Prewriting

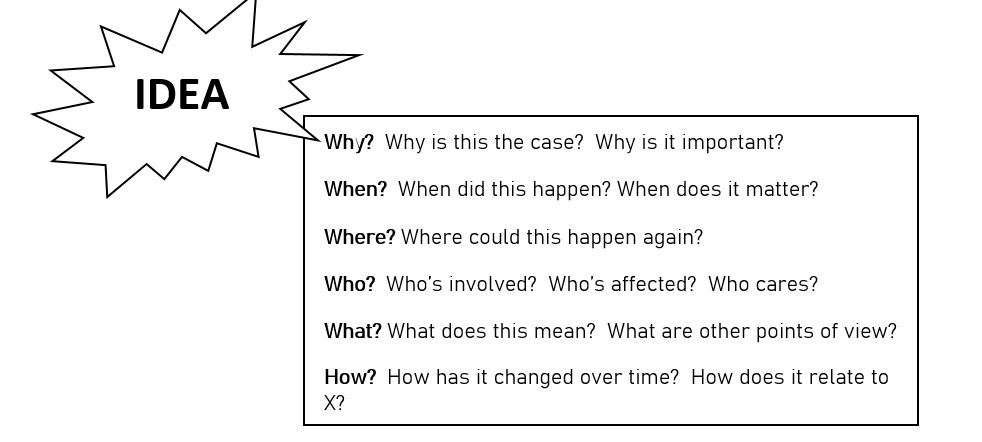

Plan the content and organization of the paper.

☑ Review and understand assignment instructions.

☑ Do initial research/thinking choose topic.

☑ Create a tentative thesis.

☑ Do further research/thinking.

☑ Make an outline including thesis and topic sentences.

Drafting

Write the ideas in sentences and paragraphs

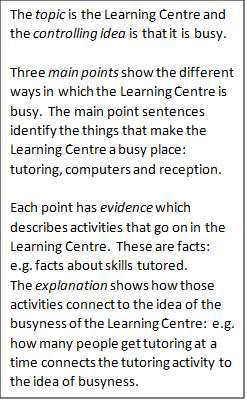

☑ Develop body paragraphs each with a main point and evidence.

☑ Write introduction to interest reader and establish focus of paper.

☑ Write conclusion to summarize paper and explore implications.

☑ Create list of references used.

Revising

Further develop content and organization by asking yourself these questions as you revise.

Focus

☑ Identify the focus of your paper.

☑ Evaluate the thesis statement. Does it clearly state the focus you’ve identified?

☑ Mark parts of the paper that do not directly relate to the focus.

Organization

☑ Identify the topic sentence of each paragraph.

☑ Identify the paragraphs that serve as introduction, body and conclusion.

☑ Create an outline of the paper using the topic sentences.

☑ Reconsider and revise the order of ideas based on your review.

- Does each section of the paper clearly link to the thesis or focus of the paper?

- Is each section of the paper clearly linked to the section before it?

- Are the paragraphs in a logical order?

Support

☑ Mark up each body paragraph:

- Circle each topic sentence and supporting point.

- Underline the specific evidence for each point.

- Put a star beside the explanation of the evidence that links it back to the topic sentence.

☑ Review your marked paragraphs to make sure each topic sentence is supported by main supporting points.

☑ Evaluate evidence:

- Are there any gaps or errors in logic which cause the support to be less than convincing?

- Are sources of information credible and documented?

- Is there sufficient specific evidence (e.g. examples, statistics, description, quotations) for each point?

☑ Make sure the evidence is linked to the supporting points.

Editing

Clean it up for handing in.

Language and Grammar

☑ Read the paper aloud, slowly, to yourself. Listen to the wording.

☑ Underline any part that sounds awkward or causes you to stumble while reading, and then review again to analyze those areas.

☑ List the most common types of errors that you know you have made in your writing previously. These might include these types of errors:

- language errors that make meaning unclear

- mistakes in grammar or word choice

- mistakes in sentence structure or punctuation

- sentences that could be worded more effectively

☑ Read through the paper looking for each error type on your list.

☑ Review and eliminate any biased language, shorthand, internet abbreviations and casual language.

Formatting

☑ Revisit the assignment instructions concerning the required format. Check your page setup.

☑ Go through all citations checking order of information, capitalization, spacing and punctuation with the style guide.

☑ Check that the format fits with the assignment instructions and the required style.

☑ Read paper aloud one more time.

☑ Congratulate yourself! You've worked hard to make this an example of your best writing ability.