The Research Paper

This resource takes you through the stages of developing a typical research paper:

If you are asked to do a research paper, your instructor expects you to find good information, present and interpret it in a clearly written essay and document clearly where you got the information you included. Instructors may give you specific instructions to fit their subject area.

Understanding the Assignment Instructions

The most common problem leading to poor marks is misunderstanding instructors’ expectations, so read over all assignment instructions carefully. Underline or highlight the key words or phrases that define your assignment criteria:

- steps to take to prepare

- how to organize the paper

- what requirements the instructor has. i.e. whether you are just expected to present information about the topic or you are expected to present an opinion and support it with research.

- what style you are expected to use to document your sources.

If you are unclear about any of them, check with your instructor.

Planning Your Time

Once you are clear on the instructor’s expectations, start your research paper by giving yourself a series of deadlines. Writing a good research paper is a big job; you can’t do it well if you leave it to the last minute. So, as soon as you get your assignment, look at the due date and then work backwards giving yourself a series of deadlines.

How long each stage takes depends on a lot of variables like paper length, your current knowledge of the topic, your research, your reading and writing skills, and the amount of time you can spend on the paper each week. For your first few research papers, start early.

To plan your time, follow these steps:

- Skim through this entire resource.

- Decide how much time you think you’ll need to complete each stage. Allot more time than you think you’ll need because you sometimes run into glitches.

- Plan deadlines for completing the following:

- Choosing a topic

- Taking research notes

- Making an outline

- Writing a Draft and Documenting Sources

- Revision

Choosing your Topic

Your instructor may give you a list of topics to choose from. If you need to find your own topic, there are several prewriting strategies you can use, including asking questions, making lists and drawing diagrams.

Choose a topic that:

- interests you -- you will spend a lot of time learning about the topic

- can be researched easily with Douglas library resources

Winkler and McCuen (2003) suggest that students should avoid topics that are:

- too big – if the topic is too broad, you can’t get deep enough into the topic

- too technical –you may not have the specialized background knowledge needed

- too trivial – may be not worth writing about or boring for your instructor

- over-used – it’s hard to be original about a very common topic

- too current – there may not be enough information available yet

- topics that have only one source – that’s not really research

Once you’ve chosen your general topic, the next step is to narrow it to something manageable within the assigned paper length. If you are already fairly knowledgeable about your topic, you may be able to narrow it easily. However, if you don’t know much about your topic, you need to do some general reading on your topic. Try reading about the topic in your textbook; you might also try doing a quick Google search on the internet to find basic information about the topic. Such sources are most likely too general to use as sources for your paper, but they can help you to get an overview of your topic and show you options for how you might focus your paper.

One good approach to narrowing your topic is to use Who, What, Where, When, Why and How questions to help you explore your topic. Your goal is to come up with a question you can’t answer without doing some research, but that you feel is worth answering. Such a question is often called “The Research Question”. The Research Question can guide your research and the answer you find through your research can often become your thesis statement – the main point of your paper.

Finding Sources

Now it’s time to get going on your research. Hopefully, your instructor has arranged for your class to go to the library and learn basic library research skills. If not, ask for help from a librarian.

Basic research tips:

- Check to see if your library has Subject Guides. At Douglas College, go to the Library homepage, click on “Resources by Subject” and then click on the subject that matches your course. Resources such as on-line databases and specialized websites and Encyclopedia are listed.

- To prepare to search the library catalogue or on-line databases for your particular topic, you need to identify key words, phrases or concepts you could search for. Think of different ways to state these key terms. A thesaurus can help if you have trouble thinking of synonyms. Sometimes search systems do not use the most obvious words, so think of as many synonyms for your key words as possible and then look for various combinations of those. A further complication is that the key terms that work best for one database are not necessarily the terms that work best for another, so as you switch databases, you may also need to try different terms.

- When you find a good source, use it to help you find other sources.

- Look in the bibliography of the source for other useful sources.

- Find out the key terms used to describe the good source in the database or catalogue and try those keywords to find further sources.

- The Internet is an additional way to find information. From the Google homepage, click on “Scholar” to focus more on academic sources than an ordinary Google search does.

- Don’t suffer in silence. If you spend 20 minutes and can’t find what you need, ask for help from a librarian: in person, by telephone, email, or by online chat.

- If you can’t find sources after getting help from a Librarian, you may need to adjust or change your topic.

Evaluating Usefulness of Sources

When you find sources, you need to decide how useful they are for your particular topic. This is especially important on the Internet. Use this checklist to evaluate each source:

- Are both author and date of the material provided? If not, the material may not be trustworthy.

- Is the information up-to-date? Usually instructors want you to use sources no older than 10 years, preferably less than 5 years. This varies, however, by subject area.

- Is the author or company that produced the material qualified to be an expert in the subject?

- Look for biases. Does the author have a hidden agenda that might affect the information?

- Does the author document the sources of information used to write the article? If not, the material may not be trustworthy.

- Is the information relevant to your paper? Does it provide new perspectives or new information you haven’t already found in another source?

Skimming your Sources and Developing a Basic Plan

Once you’ve found some useful looking sources, you should skim them:

- to begin to develop a general knowledge of your topic

- to make a list of categories of information you could/should include in your paper.

During this initial research phase, don’t try to do a lot of in-depth reading. Instead, skim them by reading introductions, conclusions or abstracts and glancing over topic headings and graphics. Keep a record of all useful-looking sources for later use. For more information about how to find sources, see the next section of this handout.

From what you learn in doing this initial research, you should develop a basic plan. This plan should mainly be a short list of the categories of information you think you might include in your paper. This initial plan may change as you do more research, but having an initial starting place is very useful.

Taking Notes

Now it is time to start taking detailed notes. A planned approach to taking notes can save you a lot of time later. Follow these steps:

- Before taking notes on a source, record bibliographical information for each source you want to use. This includes: author/s, full title of book or journal article, year of publication, city of publication and publisher as well as any edition number or editor’s name. For on-line sources, also include the date you accessed the material and the web address (URL). For journals and magazines, you also should record the name of the journal, the volume number and the specific date of publication. Keep a running list of the sources you want to use. Later you will organize this list and include it in your paper.

- Make a page for each of the topic areas in your basic plan. As you read your sources, put information from the sources on the appropriate topic area page.

- For each note, be sure to include which source it came from (usually just the author’s name is sufficient) and the page number.

- Your notes can include exact quotations from the sources, paraphrases of sources (putting their ideas in your own words), summaries of sources, and ideas of your own that you get from reading the sources.

- If you are copying the exact words from a source, be sure to put “quotation marks” around them in your notes so you know these are not your own words.

- Your notes do not need to be in complete sentences, but be sure to include enough information so that they will make sense later.

As you take your notes, you may find you need to add new topic areas. In that case, make a new page for that topic area and treat it like the others.

Creating an Outline

For each topic area from your basic plan, decide what points you want to make and how you want to organize the ideas. Make a simple outline for each section of your paper. The outline should include:

- the points you want to make

- the evidence from the sources that you will use to support each point.

Consider the best order, both for points within a section as well as the order of the sections themselves. Some students like to make an outline for a section and then write it before moving on to the next section. Others prefer to make a full outline for the whole paper before starting to write.

Here are some time saving tips that might help you:

- Cut up your note pages so there is one note per piece of paper. Then you can move the notes around until you are satisfied with the order. Use tape to stick them to a piece of paper to form your outline.

- Put all your notes on the computer and then just click and drag them around to create your outline.

- Do your notetaking on file cards and then physically move those around until they are in the order you want.

Using your outlines as a guide, you will write the sections of your paper in the next step.

Writing a Draft

As you write your draft, just get the ideas on the paper following your outline. Later you can go back and revise the paper, improving its content, organization, language and mechanics.

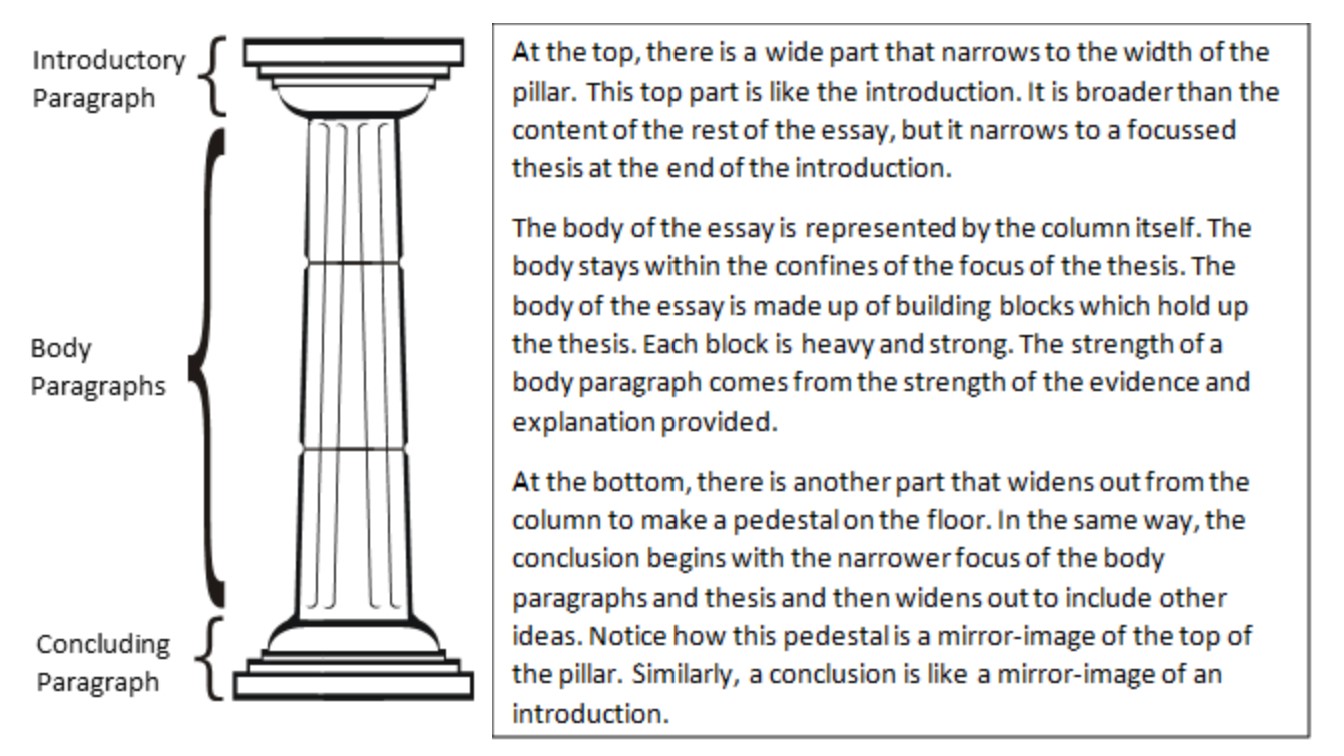

A research paper generally has three parts: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. Some students find it helpful to write the body sections of their paper before they write the introduction and conclusion. Some students just write the easiest sections first, which helps them tackle the more difficult sections later.

Remember that not all subjects are alike in what they expect in a research paper. Some areas have very specific formats that are different from the most typical described below.

Here is some basic information about each of the parts in the typical research paper format:

The Introduction

The introduction is one or two paragraphs that introduce your reader to your topic. The purpose of the introduction is to capture your reader’s interest, to provide background information, and to clarify your focus.

As a part of the introduction, you should have a thesis statement. The thesis statement tells your reader about the focus of your paper. It is the most important sentence of your paper. Thesis statements can state a point of view or simply outline the scope of the paper, depending on instructor requirements.

The Body

The body of your paper is the paragraphs that make your points and provide the research evidence. The sections you took notes on are included in the body. Each section generally will become a few paragraphs in the completed essay.

As you write, be sure to include where your information came from. You need to do that whether you quote, paraphrase or summarize someone else’s ideas. See the next section on documentation for more information about how to document your sources.

A problem some students have when they use information from sources is that they just put a whole bunch of quotes together without really discussing them. It is important to both introduce the information from your sources and follow up by discussing how the source information is relevant to the point you are making.

Use transitions and topic sentences to help your reader move from one point to the next. For long research papers, it is often a good idea to include headings in the body showing the major sections in the paper.

The Conclusion

In the conclusion, you often summarize the main points of the paper and make some comments about the significance of your topic or about actions that should be taken as a result of the truth of your thesis. Your instructor may also provide you with more specific instructions about what she/he expects you to do in your conclusion.

Documenting Sources

Documentation of sources means that you show where you got your information -- whether you quoted, paraphrased or summarized your sources. If you do not document your sources properly, you risk committing plagiarism. Plagiarism is unacceptable in college and has serious consequences.

Documentation in academic work is done in a variety of styles. These styles all basically do the same job, but they are different in the details. Your instructor may specify a particular style you should use. The most common styles are referred to as APA style and MLA style. In both these styles, you give key information about the source in brackets after you quote, paraphrase or summarize. At the end of the paper, you provide all the bibliographic information that would allow your reader to find your source themselves.

There are many other styles of documentation that are used for one or a few subject areas. Some of these styles use footnotes instead of putting source information in brackets. The most common of these is Chicago style.

When you have finished your draft, don’t make the mistake of thinking your job is done. A good paper requires more work. You need to revise your paper to strengthen its points, improve its organization and style, and check for language and mechanics errors. The following questions can help you assess and revise your work. First, concentrate on issues of content and organization. When you are comfortable with those aspects, then check the language and mechanics.

Revising: Content and Organization Checklist

- Does the paper follow the instructor’s guidelines? Check back with the original instructions to make sure.

- Is there a clear thesis in the introduction? Does the thesis fit with what you’ve written or does the thesis need to be modified?

- Does each paragraph have a topic sentence that states the main point of that paragraph? Is the topic sentence supported with specific evidence (examples, facts, logical reasoning, and expert opinion)

- Does all the information in each paragraph relate to its topic sentence? (Unity)

- Are the connections between the ideas stated?

- Have you cited sources for all ideas that you got from a source? Have you used quotation marks in all cases where you have used the author’s exact words?

- Each time you give information from a source, do you both introduce it and explain its connection to the point you are supporting?

- Have you explained the meaning of specialized terms you are using? You may feel your teacher knows what the terms mean, but generally teachers want to know that you understand those terms yourself. You show your understanding by explaining the terms in your own words.

- Does the order of the ideas make sense? Would the paper flow better if you changed the order of paragraphs or sections?

Proofreading: Language and Mechanics Checklist

Language and Mechanics include spelling, punctuation, word choice, grammar and sentence structure. There are many ways to find these kinds of errors.

- Read your work aloud slowly to find these kinds of errors.

- Use Spell Check on the computer. Note that it doesn’t catch misspellings that are also words. For example, it would not catch errors such as confusing “there” and “their” or “then” and “than”.

- Use Grammar Check on the computer. Be aware that Grammar Check has limitations; it only recognizes certain patterns and may identify things as possible errors that are actually correct. Use the underlining in Grammar Check to flag a sentence you should check yourself rather than as the last word.

- Do a Peer Review, and/or meet with a Learning Centre tutor, to help you learn to identify these errors.

Printable pdf:  The Research Paper

The Research Paper