Reading Your Textbook

The question of how to read a textbook may seem straight forward – you just open your book and read. However, there are strategies you can use that will help you get better results from your reading and save you time when preparing for tests. Because your reading is more focused, you get a lot more out of the time spent and you don’t waste time on things that are unimportant.

The question of how to read a textbook may seem straight forward – you just open your book and read. However, there are strategies you can use that will help you get better results from your reading and save you time when preparing for tests. Because your reading is more focused, you get a lot more out of the time spent and you don’t waste time on things that are unimportant.

The best way to use this resource is to apply it step-by-step to a reading assignment you need to do. So, get out a course textbook and get ready to use it. These strategies will work with both print and online textbooks.

Here are the steps for reading a chapter or section of a textbook:

- Think about your purpose for reading

- Pre-read or skim the chapter assigned

- Divide the chapter into sections

- Read actively

- Produce study material

- Study the material you’ve produced

In the following sections, each step in the process is described. Prompts in each section encourage you try the strategies by practicing the steps one at a time to help you understand and evaluate the usefulness of each step.

1. Think about Your Purpose for Reading

By thinking about your purpose in doing the reading, you can narrow down the focus of your reading and thereby limit what you spend time on. What kind of tests or exams will you need to write?

- multiple choice? You will need the ability to recognize the information on the test. You will not need to be able to recall the information on your own.

- essay tests? You will primarily need to recall main ideas. The big picture will be most important.

- application tests? This is a test where you have to apply knowledge more than just repeat back what you’ve learned. Application tests include most tests in Math as well as tests with case studies such as you get in Business or Nursing. For such tests, you not only need a full understanding of the information, but you also need practice in applying what you know.

- a mixture of the above?

If you don’t know anything about the tests you’ll write in the course, it’s worthwhile to do some detective work. If you’ve already written a test for the instructor, that can give you valuable information about the kinds of questions asked and the test format the instructor is likely to use. You can also ask the instructor about the format of upcoming tests.

TRY THIS:

Consider your purpose in reading the textbook you’ve chosen to use for this activity. What kinds of quizzes, assignments and tests will you need to write? How should that affect what you need to get out of your text?

2. Pre-read the chapter

Spend about five minutes looking over the chapter and at the items below and consider:

- What you already know about the topics being discussed. This provides hooks for your memory. It is by connecting new ideas to old ones that you can remember the new information. Your prior knowledge might be academic or it might be from life experience.

- The organization of the material; get a sense of how the reading will progress. Knowing where you are going in reading helps you organize the information in your head. This organization aids understanding and memory.

- Your purpose in reading the text.

Here are the things you should look at in your chapter. Not all of the things on the list are in every chapter, but if they’re there, take a quick look at them.

- the title of the chapter

- the introduction

- the chapter objectives (either in the text or in your course pack)

- the chapter headings and sub-headings

- any diagrams, graphs, pictures, etc.

- any marginal notes or boldface terms

- the chapter summary or review of main points

- the list of key terms

- the chapter review questions

TRY THIS:

Open your text to the next chapter you need to read for your course. Now, look at all the items from the previous list which are included in the chapter. As you look:

- consider what you already know about the topics presented

- notice the organization of the chapter

- think about what kind of test you’ll need to write on the chapter

With a classmate or peer tutor, discuss what you have learned about the chapter

3. Divide the chapter into sections

Section the chapter using the headings and sub-headings to guide you. Sections can vary in length, but the best is probably if the sections are about 2 to 3 pages long. Go on to steps four and five with the first section. Then move on to the following sections in the same way.

TRY THIS:

Look over the first part of the chapter and identify the first section you will work on.

4. Read Actively

Create questions

- Draw a line down the middle of a piece of paper. Write your questions down on the left-hand side.

- Look at the headings, sub-headings, margin notes and bold-face items, and think of questions that you think will be answered in the section. For example, if a sub-heading in a Marketing text under the major heading of Persuasion is Testimonials, a student might make questions like: What is a testimonial? How does a testimonial persuade?

- Consider the chapter objectives and/or review questions you pre-read. Do these suggest other questions about this section?

Read the section, looking for answers to the questions you identified

- Don’t get bogged down trying to understand every single thing; just focus on answering your questions. Skim stuff that does not relate to your questions.

- Use a highlighter or pencil to mark the answers to your questions or make notes on the right-hand side of the paper you wrote the questions on.

- Monitor yourself for losing focus as you read. If you notice your mind has drifted away from the reading, make a mark on the top corner of your book, and get back to the reading. Using this strategy, you will find that the number of marks reduces over time.

- Take regular short breaks. Don’t try to do a marathon reading session; that’s not very productive. A five-minute break every half hour is a good rule of thumb.

- Read sitting at a desk or table. It is much harder to focus if you are lying down or in a soft chair.

TRY THIS:

Start with the first section in your chapter. Create questions and record them on a piece of paper. Then read the section looking for answers to your questions; either highlight the answers or take notes on the answers in your own words. See the next section (Produce Study Material) for more details on highlighting and taking notes.

5. Produce Study Material

If you’ve followed steps one to four, you have already begun to produce study material. There are a number of types of study material that you can create; you need to consider which types suit your own style of learning as well as which are going to work best for the type of material you are trying to learn. Here are some options:

Highlight text and use marginal notes

Highlight answers to your questions. Put notes in the margins beside the highlighted bits. These notes should be questions or words that suggest a question. For example, if some highlighted bits suggest reasons for animal extinction, you might write three reasons for animal extinction in the margin. If the term metamorphosis is defined, you might write Define metamorphosis or What is metamorphosis?

Take notes on the section

This is similar to highlighting and using marginal notes, but it is done on separate paper and in your own words. This may seem more time consuming, but by putting the ideas in your own words, you make the ideas a lot more memorable.

A good way to make notes is to use a split-page system, drawing a line down the middle of your page. On the left, you record questions (like the marginal notes described above). On the right, note the answers in your own words. This creates a good study tool for later.

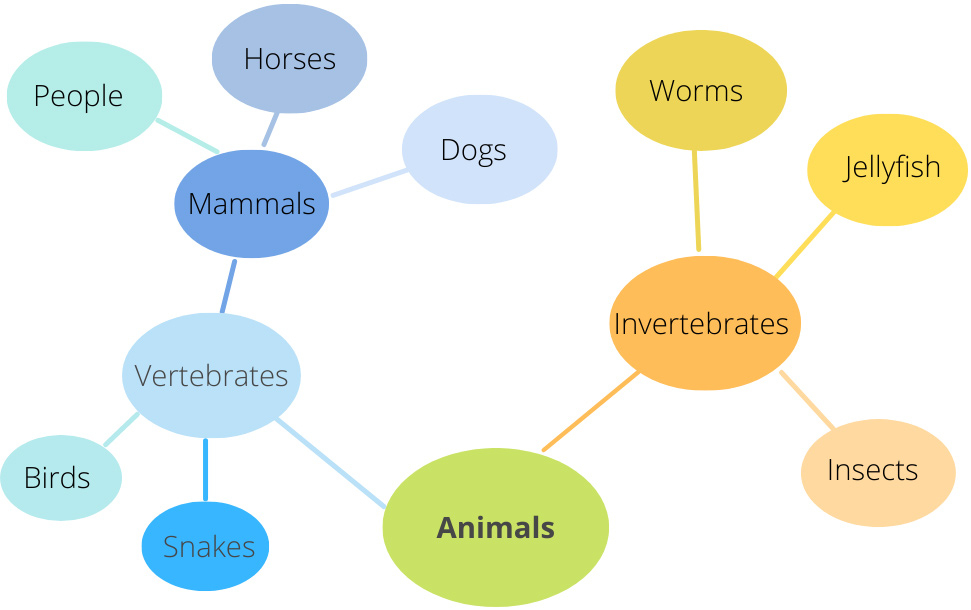

Create graphic organizers

Graphic organizers are strategies for presenting information in a visual form. They include things like charts, timelines, graphs, process diagrams, classification trees, diagrams and mind maps.

The important benefit of graphic organizers is that they look at the big picture and they encourage you to see the relationships between the pieces of information you need to learn. This aids memory.

Produce brief written summaries

Summaries are another way to look at the big picture. For each section that you read, write one to three sentences in your own words, summarizing the key ideas you discovered in the reading.

TRY THIS:

Produce at least two kinds of study material on the section you have read. If the chapter continues on the same basic topic, you may not want to produce graphic organizers until you have worked on more sections of the chapter. Continue on with your reading assignment, section by section, until you have completed it. Then produce any further study material you think would be useful. Get feedback from your tutor on the study material you have produced.

6. Study the Material You’ve Produced

Review your notes and other materials

Cover the information. Look at the marginal notes or questions and try to think of the answer. Then consult the highlighted text or your notes to check if you got the answer right.

Think of questions you could be asked about the information in the organizers and answer the questions out loud.

Read your summaries out loud. Think of exam questions that could be asked in relation to the summaries and answer them.

Plan time to study strategically

It is best to study material the first time within 24 hours of when you produced it. This makes a big difference to how much you remember. After that, the more often you review, the better you’ll remember the material. The best course of action would probably be to review all the material weekly. Minimally, you should also review it a week after producing it and again prior to writing your exams.

TRY THIS:

Within a day of completing the reading assignment, review the study material you produced. Plan when you will review it again.

Printable pdf:  Reading Your Textbook

Reading Your Textbook

This resource lists strategies for you to try to cope with procrastination. Read through the ideas to try the one that seems like the best next step for you, and then, most importantly, try it.

This resource lists strategies for you to try to cope with procrastination. Read through the ideas to try the one that seems like the best next step for you, and then, most importantly, try it.

This resource suggests strategies you can use to develop your fluency in reading and writing. Fluency is the ability to use a language quickly and smoothly and communicate ideas effectively.

This resource suggests strategies you can use to develop your fluency in reading and writing. Fluency is the ability to use a language quickly and smoothly and communicate ideas effectively.